Field Fork Fashion.

Field, Fork, Fashion by Alice V Robinson is a designer’s testament to leather — a story of the decisions made all along the food and fashion chain to create leathergoods from one single bullock.

The book was published by Chelsea Green Publishing in October 2023. This article highlights each chapter with my personal takeaways to inspire you to go and buy the book yourself. I also attended the book’s launch hosted at the Regent Street Mulberry store, so you’ll find a retelling of that evening’s discussion too.

Field, Fork, Fashion by Alice V Robinson.

Picked up my copy at the book’s launch at Mulberry’s flagship Regent Street store and swiftly started reading it on the tube journey home.

From fashion to field.

“Fashion is dependent on agriculture, and luxury fashion is especially so. From fields of cotton to wool, cashmere and silk, some of fashion’s most coveted materials are derived from a farmed natural resource. In the case of leather, it begins as the skin of an animal that (with the exception of exotics) has been reared for food by a global meat industry. This inescapable link to animal agriculture, and the associated negative impacts on animal welfare and the environment, contribute to leather being one of the most controversial materials used in fashion today.” — page 8.

The journey to using the full life of Bullock 374 for food, for fashion and for an industry-shifting narrative begins with why Alice decided to do it in the first place. From pattern cutting to womenswear design, to a specific focus on accessories, Alice was beginning to question the origin of the materials she wanted to use — or rather, needed to use, because accessory design is massively focussed on using leather (or at least it was back in 2016).

The learning curve started with great insight into an ubiquitous material; terminology, capabilities, applications… leading to an awareness of how this “lifeless” material was indeed still an animal through its markings, shape, thickness, colouration. Though as the chapters highlight, the fashion industry removes this individuality for standardisation, with Alice forging on despite barriers of infrastructure to carve a shift in ideals.

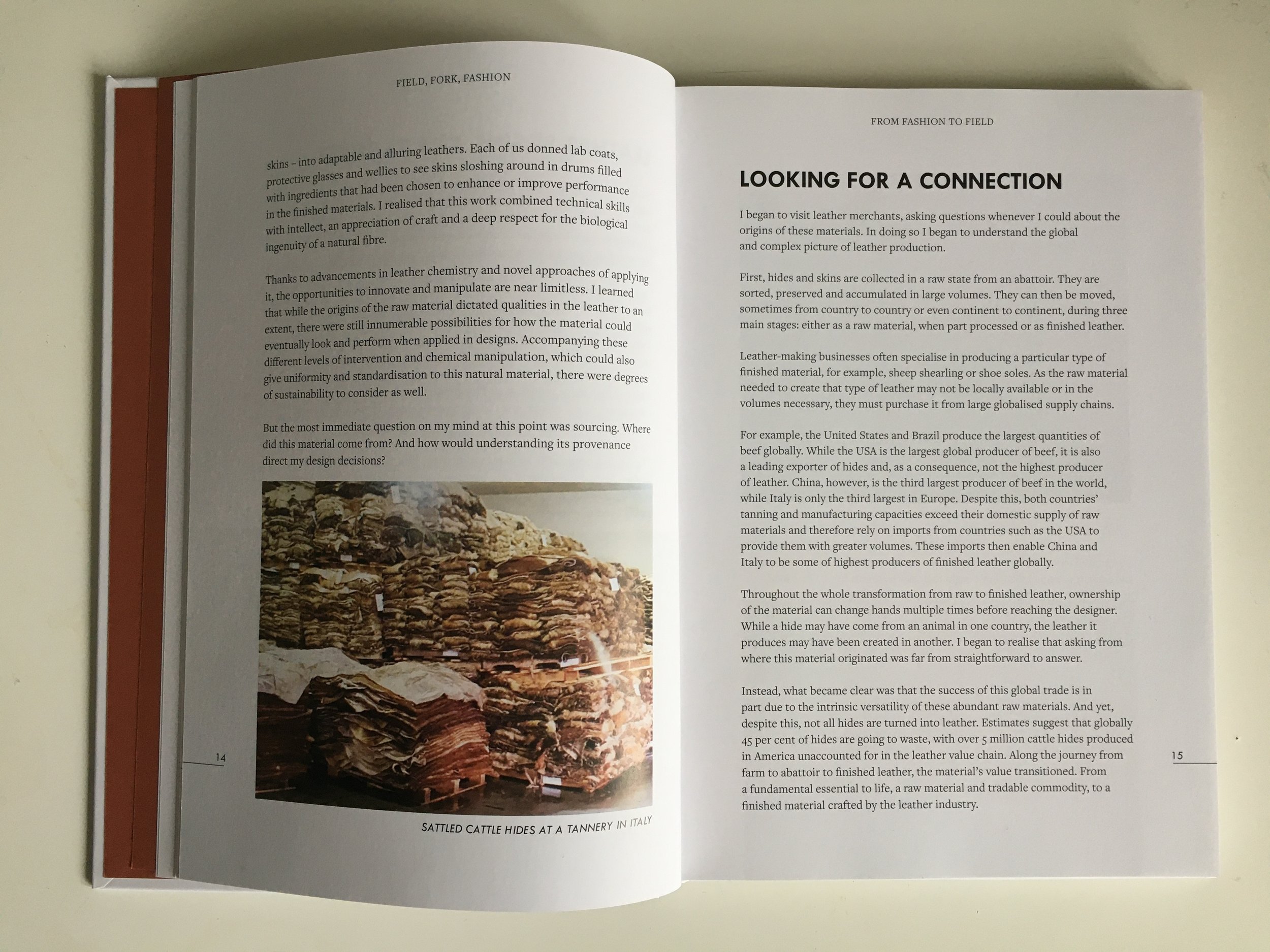

Already by page 12 (really only 5 pages in) you’re reading terms and starting to visualise how this fits with your knowledge of cows and of leather. But you’re taken on a trip to a micro tannery, through research into the global meat industry, and the personal introductions of farming life, to conceive of for yourself where the challenges lie in finding provenance.

Before taking on a whole bullock, Alice started somewhat smaller, with Sheep 11458, and here we read about the first instances of recognition for where each part of an animal goes once it has entered an abbatoir — and how a designer could intervene. This year-long project, packed into a single box, was the impetus for the V&A museum reaching out to Alice about the upcoming FOOD: Bigger Than The Plate exhibition. Though it was also the acknowlegment that as an accessories designer, Alice would have to confront where most leathergoods material comes from: cows, not sheep.

Images: 1. Title page of the book with photo of a bag created from the hide of Bullock 374; 2. Pages 14-15 on explaining the current industrial leather industry; 3. Pages 18-19 on Alice’s Collection 11458 created from a sheep.

Meeting Malcom.

“I wanted to continue my exploration into the leather industry, this time from cattle, but the scale of leather production was intimidating. In Britain alone, 50,000 cattle are taken to abattoirs each week, and globally, an estimated 300 million are slaughtered every year.” — page 31.

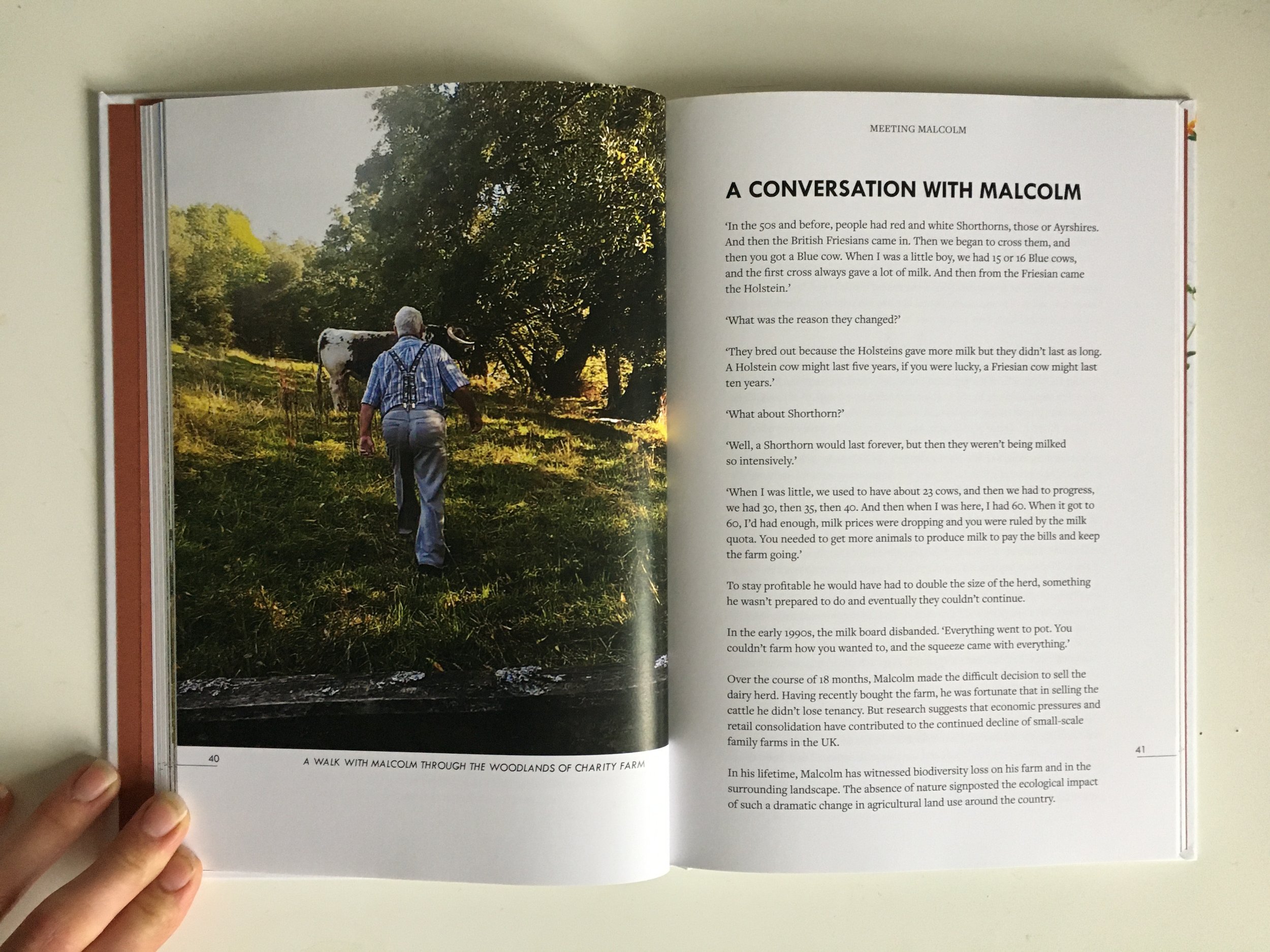

In this chapter we’re taken on an intimate adventure into small farming communities, specifically Charity Farm where Bullock 374 was reared. I initially thought of writing “where Bullock 374 grew up”, and actually feel that more apt a description than something as controlling as rearing. A great chunk of space is given over to immersing the reader into that initial meeting between Alice and farmer Malcom, allowing you to get a sense of how this system differs to the global industrialised system.

Just imagine if every single thing you purchased came with such conversations; here’s your coffee and by the way here are all the life stories of those involved in its production. Ok, so we probably wouldn’t be interested when in that scenario; I sat down specifically to read a book on provenance, but tech does exist to allow for certain information to be conveyed, albeit not quite as directly relayed as a conversation.

Images: 1. Pages 32-33 on the history and personal importance of Charity Farm to Alice; 2. Pages 40-41 highlighting part of a conversation between Alice and farmer Malcolm.

Hide.

“The farm was bright and still when I arrived that morning to accompany Malcolm and the steers, including Bullock 374, to the abattoir. / Having been born at the farm, these bullocks have never, or rarely, travelled in a trailer. / The scale of an abattoir will vary depending on the services offered and the market they aim to serve — from small town or village plants that slaughter just a few animals a week to those that cater to the supermarkets and exporters processing thousands of animals daily.” — pages 49-50.

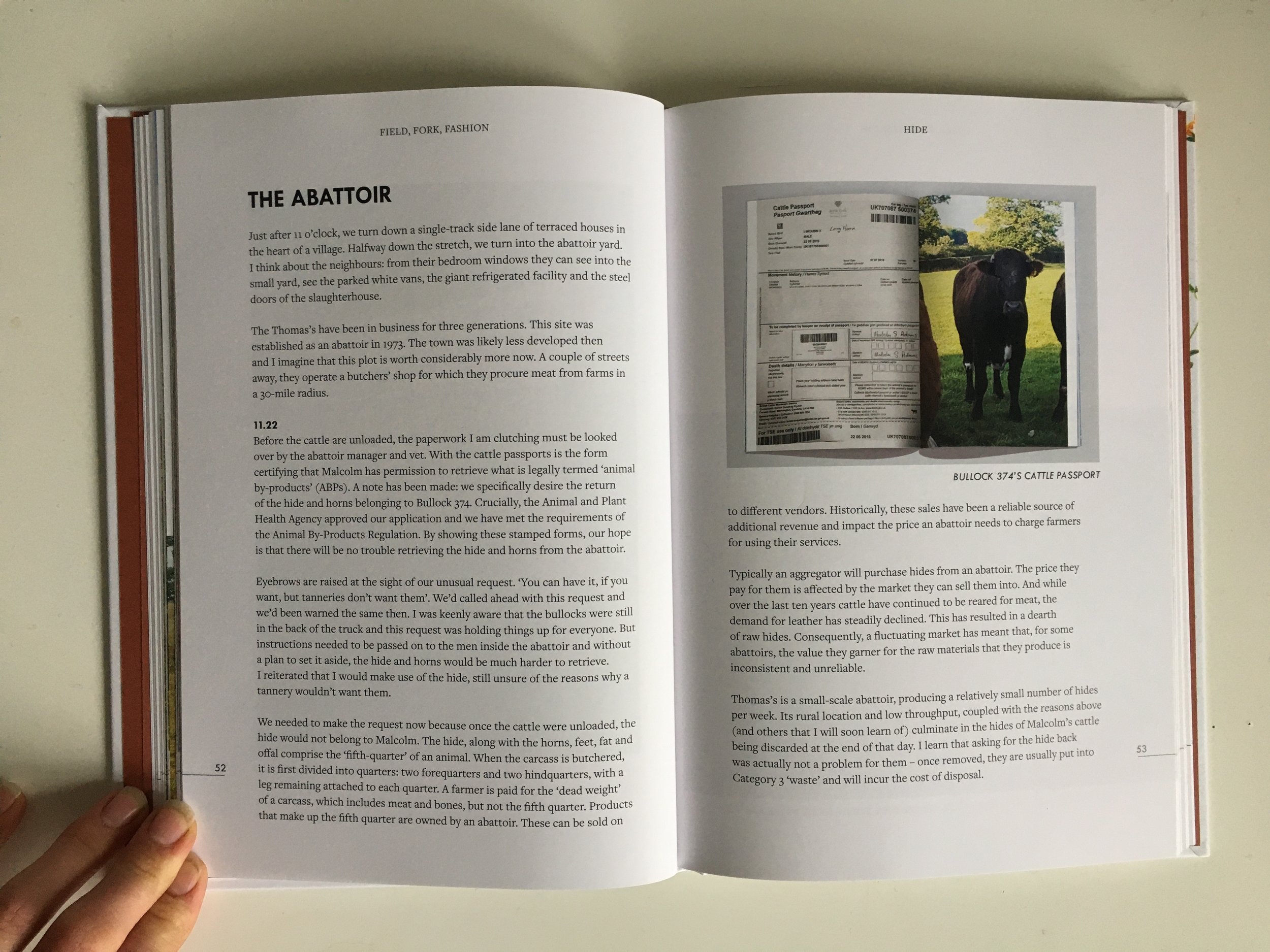

Here we learn about an abattoir set-up; how animals are transported to slaughter with great care, the variety of services and why a farmer may choose one over another, and the passport that each animal must have. We are also invited along with them to a butchers close by that will sell the meat from Malcolm’s other cattle.

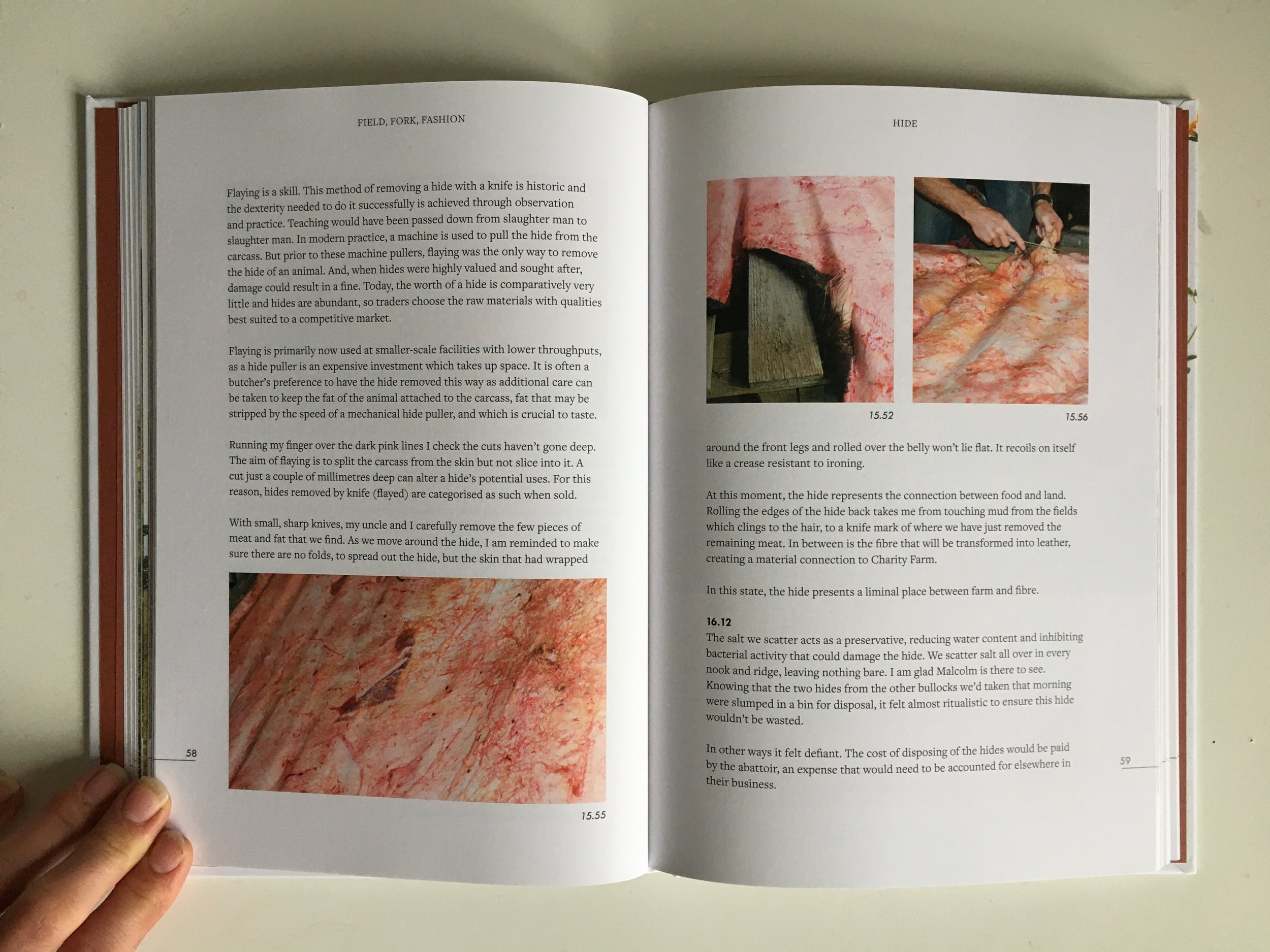

The hide collection is perhaps the part of the chain with most unknowns, especially with it being a personal pick-up. Despite not having any real idea yet how the hide will be tanned and transformed into leather to create leathergoods, Alice is already disrupting the current system by asking for a specific hide to be returned. Or, I guess buying Bullock 374 as a whole animal in the first place was radical. There’s an explanation of the importance of getting the salting right, for this will preserve the hide before it goes for tanning, along with the biological make-up of what makes a hide a hide.

The photos and descriptions are probably gruesome to our disconnected eyes and minds, but it’s utterly fascinating, and an insight we’re not privy to despite buying these materials as clothing, as food, and as cosmetics.

Images: 1. Pages 52-53 explaining the trip to the small abattoir that slaughtered Bullock 374, along with a photo of his cattle passport; 2. Pages 58-59 showing and explaining the first stages of preserving a fresh hide.

A day with John.

“I had approached this project wanting to learn about the places and people that were connected to the fibres I was working with. / I quickly realised that I had no idea what one animal could yield in the form of both food and fibre. Walking through supermarkets, perfectly portioned cuts were replicated and the same labels repeated. I’d only ever been on the receiving end of fragmented information. / I wanted to share information about the meat produced by Charity Farm and, in turn, sustain the link between farming systems, food and fashion.” — page 65.

I started reading this bit on the underground, and did feel somewhat that I needed to keep the book close, yet also wanted everyone to see. Photos showed the carcass whole, and then as cuts of meat. Alice meticulously documents at what minute and where from on the carcass that the cuts of meat were masterfully butchered.

You get a sense for the first time just how much meat can be embodied within an animal. Strangely, it got me contemplating how I would be butchered, and what material I would give. Which for sure is a strange thought, but in reality, why should I (or any other human) be valued greater than another life? The care given to highlight each stage, and indeed the portrayal of responsibility through both John as skilled butcher and through Alice as decision-maker shows the depth at which we need to reconnect with origin. We need to commit time and understanding to truly value what we are using. Cattle or human (or whatever else), everything comes from somewhere so retaining an inherent value, an energy, a lifeforce, even if it is now to all intents and purposes dead.

Stories from eaters of Bullock 374 are shown here too, with the ritual of gathering utilised to talk candidly about the food on the plate and its origin right back to Malcom and his farming practices.

Images: 1. Pages 62-63 showing a quarter of Bullock 374 on butcher John’s table; 2. Pages 80-81 depicting the inventory of cuts made to Bullock 374’s carcass.

Hold your breath.

“The natural characteristics of a hide or skin set a baseline for the type of leather it can be made into. It is this complex fibre structure, or unique weave, that is stabilised through the process of tanning, creating leather.” — page 94.

This chapter highlights limitations to the UK tanning industry, not necessarily in a negative way, but calls attention to how much commitment, expertise and relationship-building is required to go against the grain [pun intended]. Alice also explains the differences between chrome tanning and vegetable tanning, further taking you on her journey of research and design decision-making.

Technical stuff is gotten into now, and I couldn’t help but try to visualise the steps for myself to better understand how one hide can become the four pieces of tanned hide Alice decided upon. So many options are available, though many opportunities too for the variables to devastate all that went before. For instance, at each stage specific machinery and recipes are called upon that could rip or destroy the material.

I was impressed reading this section; it’s difficult to design when you don’t have materials in front of you, or at least an incline as to what you could realistically source, but Alice didn’t really know what she could design until she was holding the finished leather. Just like any textile artist (or now lab biotech scientist) creating a material from scratch, here Alice was designing, just not in the way we’re trained to at university. At any stage you’d need to be willing to shift your ideals based on what the outcome was. Designers after all are problem solvers, but nowadays everything is handed to you in multiple options, minimising the chance to come up with an original solution.

Images: 1. Pages 98-99 that start to explain and photograph the pre-tanning stage; 2. Pages 104-105 explain the dressing stage with a diagram of the fibre types present in a hide; 3. Pages 110-111 shows suede being napped and this texture contrasted against leather.

A month of making.

“I laid the long edges of the full-grain and hair-on side next to each other and the hide became whole again. This was my first opportunity to take a closer look at the leather.” — page 115.

I’d already been flabbergasted frankly at reading “a month of making”, wondering (with my own experience in mind) how to design and create luxury goods in that timespan. Alice had only just been reunited with the hide and then had to swiftly decide how to cut it up, with no going back once that process had started. I’ve dabbled in zero waste pattern cutting, though I expressly chose to use geometric shapes that would allow for not only minimal waste but ease of design too (or was it restrictive, because I could only essentially use squares and triangles?)

Though I’d seen the Bullock 374 collection in person at the V&A, and again at the book launch, here reading this chapter I was again impressed and amazed at the phenomonal outcome. Envisioning the headaches that must’ve ensued trying to choose a range of products to fit these leathers, and the worry of physically making a cut… sickening responsibility.

You read about the proof of life and “imperfections” of the leathers, marks caused when Bullock 374 was grazing, or when the hide went through its processing. Along with the characteristics of the leather as a shoulder bit or spine bit or belly bit, and as full-grain leather or as suede or as hair-on, these surface marks and cuts would have to be considered in the design — both to emphasise the living material and to ensure a durable product.

There’s also technical details in how you construct leather materials into goods, which played into decisions on designing for minimal waste. 3D patterning software helps designers today in visualising their pattern pieces, which probably helps in reducing sample waste, though because this was still in its infancy at universities when I started studying (2007), the thought of using software feels more alien than simply drawing on a material. Regardless of how valuable I felt the materials were that I used in my collections, I was never holding something that I’d seen alive, unlike Alice’s leather. So again, mindblown at what she created (with the aid of Stephanie the leatherworker).

When it comes to waste, my eyes lit up at how leather offcuts were embedded in the shoe soles in replacement for not having had shoe leather available. And the selection of horn and bones for trims is a beautiful addition. I wondered if, in doing something so full-bodied again (or someone else taking on the mantle), they’d reclaim all of the bone waste from the butcher rather than a small selection. Nowadays we see a resurgence of such materials as bone china, or indeed more contemporary materials using bone dust as the raw ingredient. But these specific pieces retained were described as having the “most obscure grooves and curves, ones with a scale that suggested their origin”.

Using an embossing stamp, finished items were branded with the bullock’s number, the date of slaughter and the postcode of Charity Farm: 374 09.10.18 LL13 OBW. A luxurious and intriguing way to pass on information.

Images: 1. Pages 116-117 talks about the natural characteristics present in unfinished leather with a photo of scratches on 374’s leather surface; 2. Pages 130-131 transcribes the pattern lay of each leather/suede piece and corresponding leathergood; 3. Pages 132-133 are all of the finished pieces laid out (I was impressed even with how this box was made).

British Pasture Leather.

The epilogue is written by Sara Grady, friend and business partner to Alice, also on the journey of disrupting and shifting the existing industrial meat and leather industry, particularly in the UK (hence the name). It tantalises you with hope for what a more transparent, traceable and regenerative food and fashion system could look like for materials specifically from agricultural systems, such as leather and wool — but even outwards to ones not livestock-oriented (silk, cotton, flax, hemp).

It provides an opener to the reader to consider how animals can be integrated in farming systems to improve nutrient, water and carbon cycles, and how those animals could be better respected in the fibre and fashion industries. Though both are relatively recently formed, British Pasture Leather and Alice’s two collections are proof of concept that the industry can be amenable if you put in the commitment to build relationships, respect wisdom and are willing to collaborate.

Images: 1. Pages 142-143 start explaining the next stage of research and proof of concept of a leather industry (and farming) shift; 2. Pages 146-147 gives photos that connect the historic UK tannery where British Pasture Leather is made and luxury fashion items made from that leather.

Book launch at Mulberry.

Arriving into the space I felt totally out of place, but did my best to shirk off insecurities. I wanted to touch stuff, but these places give off a museum vibe. Careful not to spill my gin and tonic as I moved around, and checking for any oils on my hands, I did stroke the pieces from Collection 374 and took in visually as many details as I could. Though I’d seen them at the V&A, I was no longer new to the project and was better equipped to connect the research and design journey with those finished products. Plus this was a shop not a museum and the items were laid out openly. That being said, I still wouldn’t willy nilly start trying stuff on, and perhaps that’s because I know the full extent of where they originated; would someone without any really context handle them so carefully as if they were museum pieces?

Images: 1. Alice in a madder-dyed two-piece outfit from Phoebe English; 2. The book on display next to a bag from Collection 374 made out of leather; 3. Alice’s lovely message in my book copy.

Sara Grady gave an introduction before fashion critic and columnist Sarah Mower interviewed Alice about the initial research, the process of writing of the book, and the next steps of British Pasture Leather. The audience — made up of fashion industry folk, leather specific folk, and a variety of landworkers/farmers — then were able to ask some questions.

As I always find, Alice was eloquent and pragmatic in her responses, carefully crafting her sentences to be clear yet evocative. Holding herself with grace (and dressed in a very classy madder-dyed Phoebe English outfit) Alice exudes luxury, which can only be of benefit when attempting to shift the minds of luxury fashion houses. And yet she’s also witty and charming in a very genuine way, a characteristic I’ve had the pleasure of being on the other side of when interviewing her for various discussions and panels.

I didn’t make enough notes because I was engrossed in the conversation occurring then and there, but key points were:

Meeting others in a room from a different sector opens opportunities for sharing problems. Until you go to someone in a seemingly unrelated industry, how would you know that you could help each other out? And that would likely be the case for many areas, not just food and fashion, because systems cross over.

We can’t really discuss global scaling to meet needs, because it’s realistically not what our earth (or people or animals) has capacity for. Scales need to shift to suit regions and seasons. Examples of local collectives in Germany and Oregon (USA) were mentioned that are doing similar research in practice.

There are barriers when it comes to communication of this work, and funding to do both the work and the communicating. But designers and brands have shown receptivity. There’s also murmurs of changes to curriculums and courses, with the implementation of one solely on systems change at the Royal College of Art.

Images: 1-6. Pieces from Collection 374 on show at Mulberry’s flagship store. Top row L-R: Suede coat with leather belt and bone + horn buttons, purse using full-grain and hair-on leather with bone hardware, knee-high boots in full-grain leather. Bottom row L-R: sole of the knee-high boots (with leather offcuts embedded in the rubber sole) with metal ‘374’ plaque, hair-on leather cropped jacket with horn button, small handbag in hair-on leather with embossed leather patch and bone hardware (sat next to suede coat).

The hardback book is available to purchase from all sorts of places. Get it directly from Chelsea Green.

Thank you for reading.

You may also like the following:

Regenerative leather at Groundswell.

Rethinking waste (food + materials).