Regenerative cotton farming.

Regenerative cotton farming requires a systems shift. It requires commitment, experimentation and foresight from those in the cotton value chain to recognise what regeneration looks like for an agricultural commodity and how to practically implement it.

This article uses a presentation and panel discussion from Threads of Change — a five-day natural fibre festival in London — as the starting points to open up some areas of insight into cotton farming regeneration. At the end there are additional key resources to direct you to further reading.

Read about the Threads of Change exhibition on natural fibres.

Commodities, value and traceability.

The point to start with is that while cotton sits within the textile industry, it is first and foremost a commodity crop that has a value chain.

Commodity crops are plants that are not grown for direct consumption but for sale to a commodity market. They’re described as being grown in large quantities and stored because they are non-perishable and indistinguishable from each other — though I believe there would be a use-by date for coffee cherries. These commodity crops will have been shipped across the world, and likely end up in our food system in some form, but not necessarily the initial harvested crop.

Cotton is harvested from the shrub as a boll containing seeds. The boll is the fluffy bit and is used for cotton fibre. The seeds are pressed for vegetable oil for human consumption/cosmetics, with husks made into cakes as an agricultural feed. This is what a value chain is: how products are made into more products.

So you can already start to recognise how complex it is to shift an existing system when all the offshoots need to be considered too. And that’s where traceability and transparency come into effect with cotton; how can you monitor that a regenerative fibre stays as what it’s labelled as, not bundled up with non-regenerative (conventional) fibre? Traceability considers how you manifest the tracing of something, while transparency considers the communication of that data.

Vertical integration i.e. a company that owns mills and facilities for each step, or otherwise certification i.e. to provide frameworks and testing, are really the only ways to get some handle on it. Even with the implementation of tech such as blockchain or simple QR codes, the physical crop/product cannot be labelled and can be mishandled. There are instances of cotton fraud.

Images: 1. A cotton field in Austria [Credit: Trisha Downing on Unsplash]; 2. Shree Ram Fibres ginning; 3. Ihsan Pakistan spinning mill.

Raddis®.

Who are they?

Raddis® is transforming the cotton value chain with a transparent “farm-to-product” system creating fibre, yarn and finished garments. Initially an arm of Grameenas Vikas Kendram — a society that facilitates and creates sustainable agricultural business and marketing models — Raddis® has been standing apart and providing opportunities for change, and have proven clients.

GVK society focusses on food crops specifically, with Raddis® concentrating solely on cotton. It stands for Radically Disruptive. To start to understand why the cotton chain needs disrupting, here are some widely known statistics:

27 million tons of cotton are produced each year. Most of our clothes are made from conventionally produced cotton that uses massive amounts of pesticides and freshwater.

More than 300,000 farmers have committed suicide in India since 1995, because of huge debts related to pesticide, fertilizers and seed suppliers combined with disappointing crop yields.

2 billion T-shirts are sold per year and each t-shirt takes about 2700 liters of water if made from conventionally grown cotton.

Only 1% of cotton trade is grown organically. Rising demand for this 1% of organic cotton is causing huge price increases, bigger earnings for the middlemen, and boosting fraudulent activities around certifications.

How are they different?

Aneel Kumar Ambavaram is the head of GVK as well as the founder of Raddis® and he recorded a chat that was presented on day two of Threads of Change for the conversation on how climate change affects cotton farmers. I had the privilege of speaking with Aneel and colleague Sanne van den Dungen a few years ago for an interview; it ended up being a couple hours and whoppingly insightful. But I’m no longer at the business they were recorded for, and they’re behind a paywall so can’t share. A key takeaway was how Aneel was previously a pesticide salesman, and that revealed to him what was occurring literally on the ground to farms and to farmers.

He established a new business model for cotton trading called the “circular cotton cascade”. It calls for disruptive innovation, plural value propositions and closing the loop on cotton in the biosphere. Conventional cotton farming perpetuates poverty and pollution, and doesn’t have circular value chains, for example because biomass is burned. His presentation ran through how they are already working on these challenges, and what their five-year vision was.

How do they work?

GVK as a whole work with 20000 farmers across 938 villages. Raddis® work with 4139 farmers across 388 villages and 5200 acres, focussing on the Andhra Pradesh region in India, and particularly with farmers earning less than $2.5USD per day. They look to:

regeneration of ecosystems and smallholder businesses;

value addition for all parts of the land not just the crop i.e. interplanted vegetables;

collectivism through nurturing successful farmer producer organisations (FPOs i.e. a sort of co-operative that bands together to improve their market positioning);

and up-marketing by introducing certifications e.g. Regenerative Organic and GOTS, plus selling finished products to the international market.

Some ways that they are holistically addressing barriers for farmers include:

inclusivity of female tribal farmers and resource-poor families that may otherwise not receive any support;

interventions beyond the farmers, such as implementing a seed bank and wider climate mitigation tactics;

looking to other aspects of the value chain i.e. introducing a ginning mill, an oil-seed extraction unit, a hand-spinning unit, and a natural dye unit;

working with other organisations and charities for funding, awareness, support e.g. Heifer International (nonprofit working to eradicate hunger), Women On Wings (supporting women into employment and training) and Commonland (for landscape restoration).

Images: 1. Training farmers in natural fertilisers; 2. Farmers intercropping plants to boost soil nutrients, microbiome and biodiversity; 3. Cotton plants from Raddis-provided seeds newly germinated.

How is the cotton used?

Of course there needs to be a market for this crop specifically grown regeneratively and marketed as such. The cost is higher, there’s a commitment of time required (because growing is seasonal, slow and unpredictable), and you’re investing in a system rather than a finished product. It’s not like we can go and select some regenerative cotton fibre to do our own thing with; it needs to be purchased from the market as a spinning mill, or as a brand who’ll take it to the spinning mill.

Surprisingly, they already have a big hitter on their client list: Hugo Boss, plus smaller brands including Bedstraw & Madder, HAKRO and Lässig plus Trimco Group (for RFID supply chain traceability).

Aneel says that their farmers are already earning 30% more income (though they want to increase that to 50%). This is because they offer zero interest on inputs (seeds, fertilisers), the cultivation costs are lower (e.g. no pesticides), farmers access diversified incomes, and a market premium for their regenerative organic crop. On top of this, they have established 2 FPOs, which means they have a greater market standing (i.e. control) as well as ecological benefits from not using GM (genetically modified) seeds and pesticides on their 5200 acres.

What’s next?

I’ve made a note of some numbers that I think refer to what they anticipate for the coming year, which is working with 600 villages, 7520 farmers and consequently on 10000 acres. Their five-year plan looks to eliminate GMO across 25000 acres, increase biodiversity by 100% and double the income of 12500 households.

Images: 1. Woman holding a large handful of freshly-harvested cotton bolls, standing on a barren piece of land (which actually I feel doesn’t enhance the vision of regen cotton) [Credit: Hugo Boss x Raddis]; 2. Sanne van den Dungen and farmers/ginners sat on cotton bales with a Raddis banner. [Credits: Raddis® Cotton]

The economy of cotton production.

Jui Gangan is an advisory board member for GVK, the Director of Global Partnerships for Raddis, and a business advisor for Khadi London. For this discussion during the festival, she sat down with Jo Salter, another female Director of Khadi London and social entrepreneur, to discuss impacts Raddis farmers are facing. Though the discussion was scheduled to look at the impact of climate change, it was geared towards the nuances of how climate change are affectual in an agricultural setting, particular towards gaining funding and receiving income. There were points made I had never considered, so it was illuminating and I appreciate Jui’s practical insight.

Indian context.

In 2012, Raddis was working with 25 farmers, and so went to Jui for advice on gaining investment to, in a way, scale. But scale is all relative; in an Indian context, 90% of land is owned by private landowners with tribal communities essentially renting the land or working as labourers. The work then is not necessarily to shift who owns what land, but to improve the land that exists, which to Raddis meant focussing on the soil first, with a consideration for cycles and seasons.

With the majority of farmers in India being tribal, they do not have a birth certificate and therefore cannot open a bank account. So even if they were able to sell to the cotton market, how would they receive their money? ‘Farm Passes’ from Mastercard help to digitise the farmer. For £10 per person, as a one-off lifetime fee, farmers are able to be digitised and open a bank account so they can trade. This simple investment is already a step towards increasing capacity, provides autonomy to the farming communities, and consequently opens doors for the creation for Farmer Producing Organisations so farmers can have more market control.

Brand investment.

Unlike the current textile and fashion system where a brand simply selects a certain amount of fabric to make a certain amount of pieces to bring in a certain sum of profit, the regenerative cotton farming model requires an almost backward approach. The brand ideally knows how many pieces they want to offer, which is the starting point, but that ‘regenerative cotton’ is not yet available on the market. If they wanted organic, they could easily find a spinning or fabric mill to purchase from, regardless of organic contributing only 1% of cotton fibre production. Regenerative, however, is still in the stage of transition, necessitating not only the tracing of the crop to fibre but also an agricultural practice and an economical model.

The brand then needs to pay for the amount of farmers required to work an area of land that will grow an amount of cotton crop, that can then be processed into a traceable regenerative (organic) cotton fibre for production into textiles and fashion products. It’s a question of capacity, and they need to be willing to pay up front in commitment to purchasing a certain amount of crop, and in turn paying the farmers growing that crop.

However, brands tend to pay 40% of the product cost upfront, which means (at least for the Raddis model) there are 10-12% of missing funds required to achieve the growing and processing capacity. This needs to be found somewhere. Interest rates with banks are currently around 35%, so for an organisation to then borrow that 10-12% with that interest rate, it’s unsustainable. Brands therefore need to invest that little bit extra to remove pressure from the organisation. Which is a difficult ask if you’re indeed a small independent label, rather than Hugo Boss. So perhaps here it’s about larger retailers taking the hit so smaller designers can get their foot in the door. As the final fibre cost is higher (than a conventional cotton fibre), brands using Raddis are currently European or US-based as they have the consumer market for a higher end price point.

Another issue with investment regards commitment to a sort of decentralisation or otherwise (more) local production. Jui’s example showed Hugo Boss purchasing the processed cotton fibre/spun yarn, but still exporting it to Bangladesh for garment production where labour costs are lower, and then on to Europe for distribution. While there is a shift towards a more regeneratively economic model by supporting an organic farming system and consequential farmer control, the textile and fashion system remains global and remains a space for driving down costs.

Jui did say that any brands interested in Raddis cotton don’t question the funding investment required once they have seen the farming system on the ground. But once they’ve received their fibre, they’re out of that Raddis structure and can simply lessen margins elsewhere.

Regulations.

This is a complex area for me to get my head around, so frankly haven’t really considered it before. But the barriers in selling to the cotton market, and then import/export of that cotton (at whatever stage in the value chain) can be further complicated by what regulations are in place in the country you’re growing in/processing in/procuring from. Everytime a product of the commodity moves, it requires compliance paperwork.

For smaller producers and for smaller brands, this governance affects their capacity. It stands to reason as a brand or retailer that if you can do less work by operating in one country over another, you’ll likely do that (especially if those countries have also reduced their costs because they’re not paying for this governance compliance time). Raddis consequently have dedicated staff for compliance (through monetary donations) so that their farmer capacity can continue to improve, and therefore the regenerative model too. Presumably this means that if you’re a farmer producing on your own, it’s simply too difficult to monitor everything, and you can’t shift how you operate to anything more sustainable for your family.

The recycled t-shirt.

Of course, to sell the concept of a system shift to brands and retailers then a finished product is useful. You can’t obviously travel a farm across the world, but you can take some cotton products to help highlight what can be created from your investment.

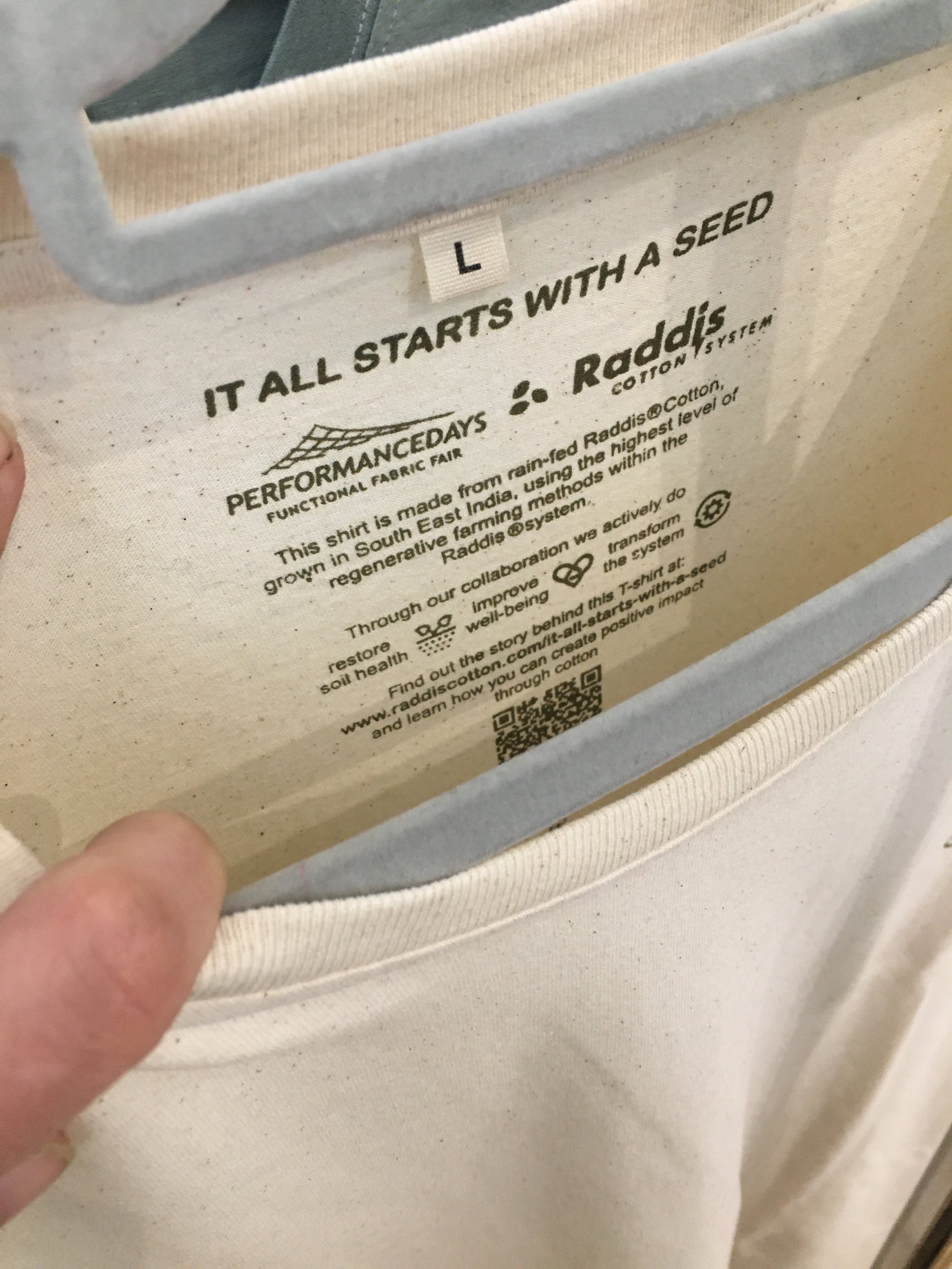

Jui brought with her for the Raddis exhibition stand some t-shirts that had been produced for the Dutch festival Tomorrowland. They purchased 10000 t-shirts, and for the following year, had them mechnically shredded and recycled into a new fibre of this 70% post-production waste with 30% virgin regenerative cotton from Raddis farms. It stays a Raddis regenerative product, contained in the Raddis economical model, but is providing yet more value to an existing valuable piece. The t-shirt explains where it’s come from, and comes with a paper product passport that has a QR code to show the t-shirt’s journey. One key issue is that the recycling is currently done in Europe then shipped to India for reprocessing as fibre and as product.

My query was regarding traceability. Jo had mentioned transparency, though this isn’t the same as traceability. As far as I know, and alluded to previously, fraudulent claims are occurring from organic fibres and conventional fibres being mixed up, particularly at the ginning stage before fibre is even obtained. Once bundled up, there’s no visible way of noticing if a cotton is organic or conventional (or indeed from a regenerative model). Companies like Oritain are using forensic science to confirm origin, though this is always retrospective. A product passport is therefore lovely, but it’s not confirmation.

Jui responded that there is third party data collection (self-initiated by Raddis and by brands), complying with the GOTS organic certification framework. But unless the processing run is completely halted for the processing of this ‘regenerative organic’ fibre coming from Raddis farms, I’m unsure how it can be fully traceable. She didn’t respond to my other query about when market premiums come in; something I’ve heard/read in passing is that organic actually fetches only a 5p premium, so are the Raddis premiums different to the market amount? Are they confirmed through origin? Through that compliance paperwork? This is one element of the value chain that I really want to know more about.

Images: 1. Jui and Jo on stage holding up the recycled regenerative cotton t-shirt made in partnership with Tomorrowland; 2. Details of the t-shirt’s care instructions and origin (with QR code) printed internally; 3. The paper passport that comes with the t-shirt showing how a user can trace details; 4. Indian women holding up a Tomorrowland printed t-shirt.

Additional resources:

U.S. Regenerative Cotton Fund — a Soil Health Institute initiative to encourage the adoption of ‘soil health management systems’

Better Cotton — I wouldn’t deem them ‘regenerative’ based on their membership model, but they are supporting the transition from conventional to organic farming

Regenerative Organic Certified™ — this is a certification, so not accessible to all, but for big brands such as Patagonia it’s providing a framework and the farms/processors themselves

Khamir Kala Cotton — local value chains from indigenous varities of cotton provide small-scale weavers with the raw ingredient for their craft

The Alliance of Cotton and Textile Stakeholders on Regenerative Agriculture (ACRE) — a multi-stakeholder platform that will promote regenerative practices in cotton farming by continuing to implement certification programmes